Collaborative Networks

IN THIS SECTION, YOU WILL: Understand that an architecture practice is all about people and get tips on creating organizational structures that support a practical IT architecture practice.

KEY POINTS:

- Developing an architecture practice requires having competent, empowered, and motivated architects. An an architecture practice must carefully organize, empower, and leverage scarce talent.

- In my work in the past few years, I combined two teams of architects: a small central architecture team and a cross-organizational distributed virtual team.

Good architects are a rare breed.

They bridge the gap between business, product, technology, and organizational complexity. They’re the Swiss Army knives of the tech world—part strategist, part engineer, and part diplomat. Hiring architects is akin to searching for a unicorn that can code in Python, translate vision into architecture, and navigate a cross-functional meeting with grace.

Why is this the case? Because effective architects require more than just deep technical expertise. They also need domain-specific context, organizational awareness, and the ability to build trusted relationships across the company.

So no, you can’t simply 3D print architects or hire them in bulk. But you can organize, empower, and amplify the impact of the talent you already have.

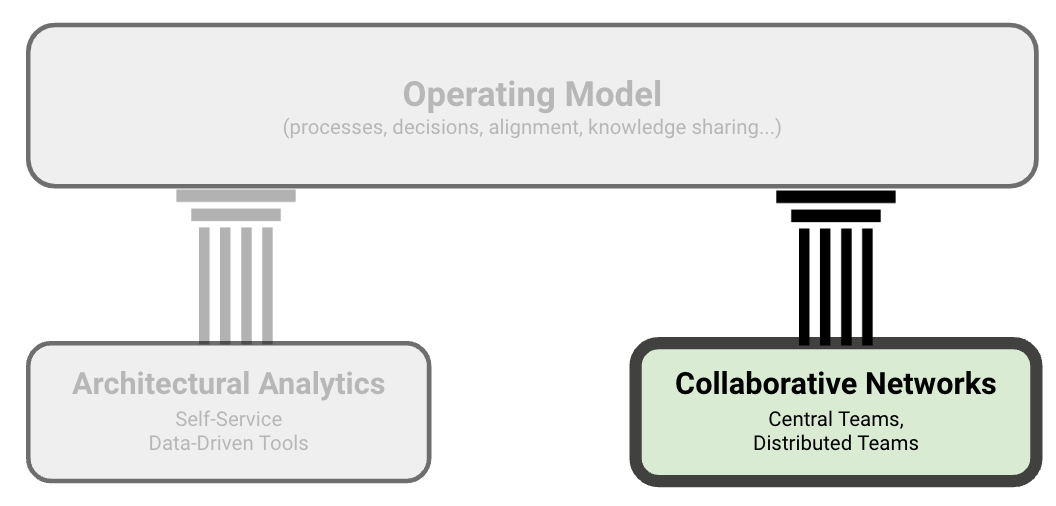

Figure 1: The Grounded Architecture framework – Collaborative Networks.

Figure 1: The Grounded Architecture framework – Collaborative Networks.

Strong Architecture = Strong Architects

And strong architects don’t work alone.

Architecture isn’t just a function—it’s a networked capability. That’s why the second pillar of Grounded Architecture focuses on people: Collaborative Networks.

Centralized vs. Federated Architecture Practice

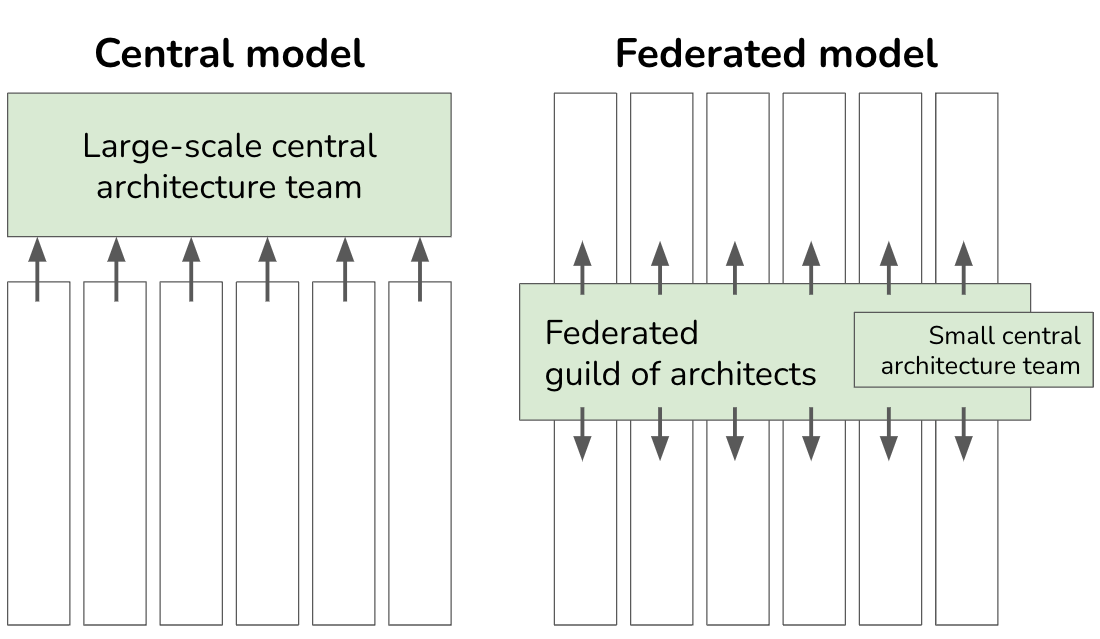

Most IT architecture practices follow one of two foundational models: centralized or federated. These models define how architectural responsibilities are distributed, how decisions are made, and how architects collaborate with delivery teams (see Figure 2, adapted from [McKinsey, 2022]).

Figure 2: Central vs. Federated Architecture Practice.

Figure 2: Central vs. Federated Architecture Practice.

The Centralized Model

In a centralized model, a large central architecture team governs most architectural decisions. This team sets standards, approves solution designs, and takes primary responsibility for infrastructure, operations, and security.

Development teams depend heavily on this central team for architectural direction, reviews, and implementation guidance. The advantage of this model is strong governance, consistency, and control, particularly in regulated or complex environments. However, it can also lead to slowdowns, bottlenecks, and disconnects between architecture and day-to-day development.

The Federated Model

In the federated model, a smaller central team—often referred to as an Architecture Center of Excellence (CoE)—provides high-level strategy, shared principles, and support, but the execution of architecture is distributed.

Architects are embedded within product, platform, or domain teams. They work closely with delivery teams, supporting planning, technical decisions, and the long-term health of systems from within. This model emphasizes empowerment, speed, and context-awareness.

It is especially common in organizations that implement DevOps practices and have a cross-functional team structure, where architecture is viewed as a shared responsibility integrated tightly into delivery.

Trade-Offs and Trends

| Centralized Architecture | Federated Architecture |

|---|---|

| Strong global governance | High local autonomy and flexibility |

| Easier to enforce consistency | Faster decision-making in context |

| Risk of bottlenecks and detachment | Risk of fragmentation and misalignment |

| Clear oversight and accountability | Stronger alignment with team-level realities |

In practice, many organizations adopt a hybrid model, which leverages centralized clarity and governance while allowing local teams to operate independently and effectively. This is where Collaborative Networks excel: they connect central architecture leadership with distributed practitioners across the organization to ensure both alignment and agility.

The Hybrid Model

In complex organizations, simply defining architecture responsibilities is not enough; you must intentionally place the right people in the right roles. From my experience, the most effective structure combines the strengths of both centralized and federated models:

- A small central architecture team

- A network of architecture guilds and virtual architecture teams

This hybrid model goes beyond a lightweight Center of Excellence (CoE). The central team takes on a proactive, enabling role—not just providing support on demand. It establishes structure, continuity, and alignment, while distributed teams offer reach, scale, and local insight.

A Coordinated Ensemble

You can think of the hybrid model as a symphony:

- The central team serves as the conductor—coordinating, setting the rhythm, and ensuring harmony.

- The guilds and virtual teams are the skilled musicians—each playing their part in local contexts but aligned with the overall composition.

Individually, they can perform successfully. Together, they create a more coherent and scalable architecture practice:

- Guilds and virtual teams enhance reach by involving more individuals in architecture discussions. They help scale alignment and surface insights from across the organization.

- The central team acts as a catalyst—connecting the dots, ensuring strategic coherence, and supporting distributed teams with tools, analytics, and cross-organizational relationships.

Central Architecture Team

Roles within the central team may vary, but it should never be treated as an isolated command center.

Instead, it should:

-

Build and maintain Lightweight Architectural Analytics: The system will not operate itself—especially not with emerging AI tools. Ownership, curation, and maintenance are essential.

-

Promote data-informed decision-making: It is not enough to simply have data; you must advocate for its use. The central team should be the example-setters in integrating analytics into real decisions.

-

Connect stakeholders: Architects need to serve as cross-organizational connectors—building bridges between departments, teams, and leadership layers.

-

Support community-building efforts: Guilds and distributed teams require coordination, rituals, and support. The central team should drive these initiatives and ensure continuity when participation wanes.

Architecture Guilds & Virtual Architecture Teams

Architecture communities—such as guilds, working groups, or virtual teams—are essential for any federated or hybrid architecture practice.

These communities typically include tech leads, staff engineers, and platform owners who:

- Act as architects within their domains

- Collaborate across teams and silos

- Mentor others and share architectural knowledge

- Drive best practices and surface challenges

They function as your peer-to-peer learning and alignment engine, helping to scale architectural thinking throughout the organization.

Types of Communities

As your guilds expand, consider organizing them into various focus areas:

- General/Core architecture teams: Address broad, cross-cutting topics

- Specialist communities: Concentrate on specific stacks (e.g., mobile, cloud, frontend)

- Strategic initiative groups: Align on larger themes (e.g., cloud migration, platform consolidation, data strategy)

Routines for Collaboration

To connect central and distributed architecture efforts, structured collaboration is necessary:

- Regular forums (e.g., bi-weekly): Share updates, raise questions, and propose architectural suggestions

- Summits (annual or bi-annual): Bring people together to reflect, align, and learn

- Ad hoc deep-dive workshops: Address specific problems and explore new patterns collaboratively

The goal is to shift from passive attendance to active participation. Architecture should be co-created, not handed down.

Architecture Is a Team Sport

Even the best frameworks will fail without a strong network of engaged, empowered individuals behind them. In a hybrid model, everyone has a role to play, and the central team exists to ensure those roles remain aligned and mutually reinforcing.

So, roll up your sleeves. Participate. Connect. Lead. Because great architecture isn’t built in silos; it’s built together.

Tips for Building Collaborative Networks

Every organization is unique, but several practices have consistently worked well for me when it comes to forming strong architecture teams and building collaborative networks. Whether you are just starting out or evolving an existing practice, here are some practical tips to guide your approach:

Start with the People Already Doing the Work

Before proposing significant organizational changes, identify and connect with the people already engaged in architecture work, regardless of their titles. Staff engineers, tech leads, platform owners, and solution experts often perform architectural roles informally.

Bringing these individuals together is never a wasted effort. It lays the groundwork for trust, alignment, and a shared understanding of architectural priorities.

Build a Team, Not Just a Community

If part of your architecture strategy includes creating a virtual team, go beyond forming an informal community of practice. Define clear roles, responsibilities, and expectations. Establish routines and rituals that foster accountability.

Architecture guilds function best when members know they are not just “showing up,” but actively contributing to something with impact and ownership.

Engage Outside the Architecture Circle

Strong collaborative networks extend beyond architects. Connect early with stakeholders outside of architecture—including product leaders, engineering managers, operations, data specialists, and finance personnel.

You will need their support, insights, and buy-in to create a practice that is integrated rather than isolated. The earlier you involve them, the stronger your network will become.

Grow from Within

Avoid hiring what Gregor Hohpe refers to as a “digital hitman.” These are external experts brought in to “fix” the architecture in isolation.

Instead, invest in developing internal talent—individuals who already understand your systems, culture, and context. The best architects combine technical depth, domain fluency, and organizational awareness, which cannot be acquired overnight.

Externalize Your Work

Don’t work in isolation. Share what you are doing—both inside and outside the company.

- Participate in industry events.

- Publish blog posts or open-source tools.

- Invite feedback on your approach.

Not only does this enhance your practice’s credibility and influence, but it also helps you attract top talent. When you showcase your architectural work, you become a magnet for others who wish to learn, contribute, and grow. Everyone wants to join the band when you are rocking the stage.

To Probe Further

- Agile and Architecture: Friend, not Foe, by Gregor Hohpe, 2020

- Crafting the optimal model for the IT architecture organization, by Christian Lilley et al., 2022

- Developers mentoring other developers: practices I’ve seen work well, by Gergely Orosz, 2022

Questions to Consider

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of people for an architecture practice, yet many organizations take architectural talent for granted. To reflect on the importance of carefully organizing, empowering, and leveraging scarce architecture talent, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you have a strong network of architects across the organization?

- Which central, federated, or hybrid model best represents your current an architecture practice? Why was this model chosen, and how effective has it been for your organization?

- If you are part of a central architecture team, how would you support the rest of the organization? How would you contribute to the global an architecture practice if you were part of a distributed virtual team?

- Consider having the roles of central architecture teams and federated architecture teams in your organization. How would they complement each other?

- How effective is the current division of responsibilities among architects in your organization? Are there areas of overlap or gaps in coverage?

- What steps has your organization taken to ensure architects are well-connected across all parts and levels? What impact has this had on transparency and the implementation of changes?

- Reflect on the diversity of team structures within your organization. How does this diversity impact the roles and responsibilities of architects?

Grounded Architecture Framework: Operating Model |

|||

| ← | → | ||