Balancing Curiosity, Doubt, Vision, and Skepticism in IT Architecture

IN THIS SECTION, YOU WILL: Understand that balancing curiosity, doubt, vision, and skepticism is essential for driving sustainable innovation and change in organizations.

KEY POINTS:

- Curiosity and wonder spark exploration, leading to technological breakthroughs. However, without caution, it can result in premature adoption of immature solutions.

- Doubt forces a critical evaluation of progress, ensuring that innovative ideas are grounded in practical and validated approaches. Over-reliance on doubt can stifle risk-taking and hinder breakthrough innovation.

- Vision and belief provide a long-term perspective, guiding efforts toward significant, transformative goals. Yet unchecked vision can lead to confirmation bias or misdirected resources.

- Skepticism helps prevent overcommitment to unproven ideas, ensuring teams remain grounded. However, excessive skepticism can result in missed opportunities and discourage creative risk-taking.

- Architects must constantly reflect on how well they balance these forces. In doing so, they can ensure that their efforts are driven by a healthy combination of exploration, critical validation, strategic guidance, and cautious realism—all crucial to achieving lasting success in any organizational change.

In today’s fast-paced tech world, IT architects are crucial in helping organizations innovate and transform in ways that are both responsible and sustainable. They’re not just bringing fresh ideas to the table; they also evaluate and guide the ideas of others, striking a balance between seizing opportunities and maintaining oversight.

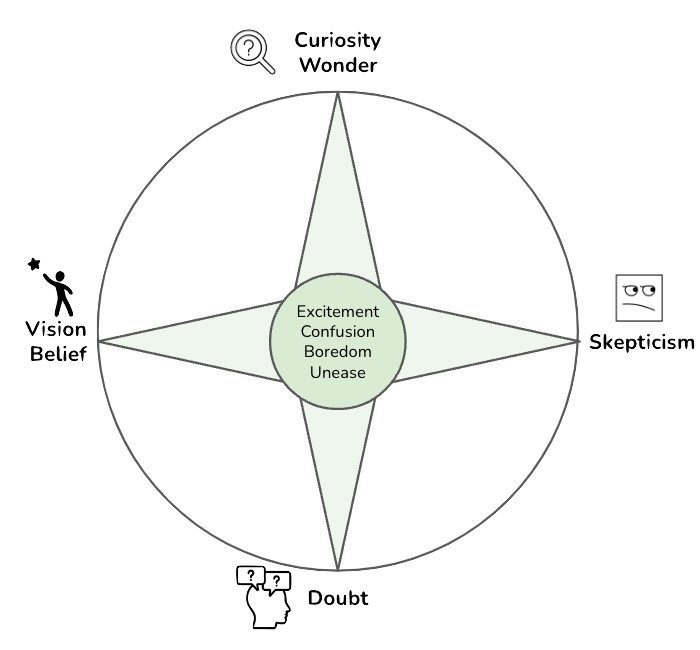

To foster sustainable innovation and navigate effective organizational change, architects need to understand the motivational forces that drive individuals and teams. Drawing from my previous research, I like to think of these forces as a compass that points to four key motivators essential for guiding responsible innovation:

Figure 1: The compass for driving sustainable innovation and change in organizations.

Figure 1: The compass for driving sustainable innovation and change in organizations.

Each direction on this compass stands for a different but interconnected motivator:

- Curiosity encourages exploration and the hunt for new possibilities.

- Doubt prompts us to reflect critically and reevaluate our assumptions.

- Vision provides clarity by linking our efforts to long-term strategic goals.

- Skepticism ensures we challenge feasibility and practicality, paving the way for sound execution.

These four forces—explorative, reflective, strategic, and critical—sometimes pull us in different directions. However, for innovation to truly be sustainable, the objective isn’t to choose one over the others. Instead, it’s about keeping a thoughtful balance among them.

Architects are in a unique position to recognize and weave these four motivators into their innovation and transformation initiatives. They play a key role in making sure that:

- Curiosity sparks structured experimentation rather than a chaotic free-for-all.

- Doubt and skepticism sharpen our thinking without putting a damper on our creativity.

- Vision aligns innovation with the organization’s broader goals and impact.

By helping teams find this balance, architects enable innovation that is both bold and grounded, strategic yet adaptable. This delicate equilibrium empowers organizations to pursue change with both imagination and discipline, a combination that’s essential for long-term success.

In the upcoming sections, I’ll dive deeper into each of these four forces, showcasing how they influence innovation and how architects can effectively activate and harmonize them within their teams and across the organization. Let’s explore this journey together!

Curiosity and Wonder: The Spark of Innovation

When we think about what drives innovation, curiosity and wonder often stand out as some of the most powerful motivators. Curiosity is that innate desire to explore, understand, and ask, “What if?”—and it’s a crucial force behind technological progress.

In vibrant engineering cultures, curiosity isn’t just welcomed; it’s nurtured. When organizations foster autonomy, exploratory freedom, and space for experimentation, they create fertile ground for curiosity to flourish—and guess what? Innovation follows naturally.

The Architect’s Role in Enabling Productive Curiosity

It’s interesting to note that architects—who often play a pivotal role in guiding innovation—can sometimes lose that spark of curiosity over time. They might find themselves bogged down by reviewing others’ ideas or focusing too much on risk management. But the best architects embrace their role as curious catalysts. They leverage their wide-ranging knowledge to explore and assess emerging technologies with intention and purpose.

Architects hold a unique position to drive responsible exploration—it’s about more than just following trends; it’s about understanding their implications and potential impacts.

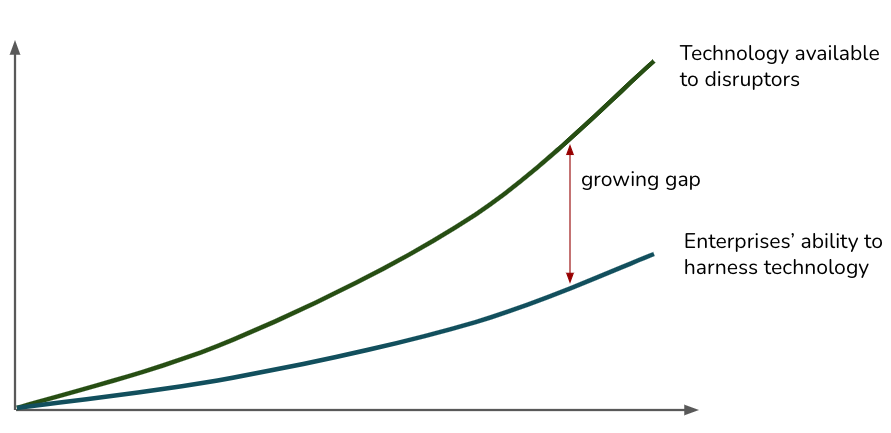

According to insights from ThoughtWorks, there’s a growing gap between the pace of technological change and how quickly organizations can adopt these changes. When organizations don’t keep up, they’re not necessarily lacking in innovation; instead, they struggle to absorb and apply new ideas in a sustainable fashion.

Figure 2: Technology advances exponentially, but organizations struggle to adopt at the same pace. Curiosity helps bridge this gap. Source: thoughtworks.com

Figure 2: Technology advances exponentially, but organizations struggle to adopt at the same pace. Curiosity helps bridge this gap. Source: thoughtworks.com

The Double-Edged Nature of Curiosity

While curiosity is a fantastic driver of progress, it can also lead teams astray if it’s not kept in check. If we dive headfirst into emerging technologies without a critical eye, we might end up with naive solutions, overcomplicated systems, or unnecessary technical debt.

To strike the right balance, curiosity needs a counterweight—like doubt, skepticism, and a long-term vision—so we don’t end up chasing novelty for the sake of novelty.

Real-World Examples: Curiosity in Action (and It Risks)

Here are some real-world examples of how curiosity has spurred meaningful innovation, along with the pitfalls that sometimes come with it:

Microservices Architecture

- Innovation driver: Curiosity about modularity and scalability gave rise to microservices, offering flexible deployments and cloud-native ecosystems.

- Sustainability risk: Teams that rushed into microservices without the right tools or operational readiness faced increased complexity and performance issues.

Serverless Computing

- Innovation driver: Developers eager to reduce infrastructure burdens pushed the adoption of serverless architectures.

- Sustainability risk: Those who didn’t consider factors like cold start times or vendor lock-in often ran into performance bottlenecks later.

Agile Methodology

- Innovation driver: The desire for quicker, more adaptable workflows fueled the rise of Agile.

- Sustainability risk: Misusing “Agile in name only” created chaotic environments without actually improving outcomes.

Blockchain in Software Development

- Innovation driver: The attraction of decentralization and security ignited experimentation in numerous non-financial areas.

- Sustainability risk: Occasionally, blockchain was applied where more straightforward technologies would have sufficed, leading to unnecessary complexity.

Final Thought: Channeling Curiosity with Purpose

Curiosity is vital for maintaining relevance and competitiveness—it’s what drives learning, experimentation, and innovation. But curiosity on its own isn’t enough. We need to pair it with critical thinking, thoughtful evaluation, and strategic alignment.

Architects have a key role in finding this balance: empowering teams to explore boldly while ensuring their pursuits are sustainable, purposeful, and in tune with real-world needs. So let’s encourage that spark of curiosity—but let’s do it wisely!

Doubt: The Key to Certainty and Strength in Innovation

You know that feeling you get when you start making real progress on a project? It’s exciting! But then suddenly, doubt creeps in. You ask yourself, “Is this actually right?” or “Am I just imagining these results?”

Well, here’s the thing: doubt isn’t just a nagging voice in your head—it’s one of the most overlooked yet crucial forces in sustainable innovation.

Instead of being a negative force that holds us back, doubt actually motivates us to validate our assumptions, refine our ideas, and enhance our designs. It’s that inner whisper encouraging us to ask, “Have we really thought this through?” And by doing so, it elevates the quality and reliability of our work.

Doubt vs. Skepticism: What’s the Difference?

Let’s clarify something: doubt and skepticism are not the same. Skepticism questions the entire foundation of what we’re doing, even whether it’s worthwhile at all. In contrast, doubt acknowledges that we’re on the right track but asks, “How can we make this even better?”

Doubt aims to ground our ideas more firmly, not dismiss them outright.

In fields like architecture and software engineering, doubt manifests through practices that promote quality—think testing, peer reviews, validation frameworks, and architectural scrutiny.

Building a Culture of Constructive Doubt

As IT architects, it’s essential to nurture a culture where doubt is seen as an asset, not a hindrance. When embraced constructively, doubt can lead to stronger systems, clearer thinking, and smarter decision-making.

However, there’s a catch: too much doubt can be counterproductive. If we allow ourselves to get stuck in analysis paralysis, we risk stifling innovation and avoiding meaningful risks. The trick is finding balance—using doubt to challenge our assumptions while still encouraging bold thinking.

Real-Life Examples of Doubt in Architecture

Unit Testing & Test-Driven Development (TDD)

- How doubt helps: Writing tests before coding ensures we validate behavior and minimize future failures—grounding our work in real, testable outcomes.

- When doubt goes too far: If tests become too rigid, they can discourage change and make it harder to refactor, locking teams into overly cautious patterns.

Code Reviews

- How doubt helps: Code reviews bring in fresh perspectives, catch flaws, and boost maintainability. They promote a sense of shared ownership.

- When doubt goes too far: If reviews become excessively critical or perfectionistic, they can slow down progress and dampen team morale.

CI/CD Pipelines

- How doubt helps: Automated validation checks that our software behaves correctly at every stage of integration and deployment.

- When doubt goes too far: Teams might hesitate to make big changes or embrace architectural innovations if they fear triggering failure flags in closely monitored pipelines.

Architectural Peer Reviews

- How doubt helps: Peer reviews help identify blind spots in our system design and ensure we align with non-functional requirements while minimizing long-term risks.

- When doubt goes too far: Reviews can sometimes create a risk-averse culture that discourages exploring new patterns or technologies.

Security Testing (Penetration Testing & Threat Modeling)

- How doubt helps: Security testing operates on the assumption that vulnerabilities exist, driving us to build stronger defenses and resilience.

- When doubt goes too far: Being overly cautious can hinder innovation and slow down feature delivery, resulting in overly restrictive designs.

A Final Thought: Doubt as a Design Principle

When used constructively, doubt can transform innovation into resilience. It ensures that our new ideas can withstand scrutiny—and that every spark of enthusiasm is backed by rigor.

Doubt doesn’t slow us down; it actually strengthens our progress.

But for that to happen, it needs to be balanced with curiosity, vision, and a readiness to act. For IT architects, this means creating an environment where teams feel free to ask tough questions, validate openly, and still advance with confidence.

Vision and Belief: Sustaining Transformation Through Purpose

Let’s talk about the power of belief in driving innovation and transformation. While “belief” sometimes sounds like blind faith, in our world of change, it’s absolutely essential. Think about it: meaningful change is hard to picture without a guiding vision—a strong conviction in something better on the horizon.

Vision and belief are the long-term motivators that keep us going. They fuel the energy and focus needed for big initiatives, often long before we see any results. Many architectural transformations kick off not with data or doubts, but rather with bold ideas and a strong belief in what could be.

Vision Is Direction—Not Destination

While curiosity encourages us to explore, vision gives us the direction we need. Where wonder motivates us to ask questions, belief drives us to stay purposeful and resilient. Together, they create the engine of innovation: explore widely, but stay focused.

Having a vision takes sustained effort, clarity, and the ability to lead others through the unknown. However, it’s important to remember that vision without critique can lead to confirmation bias, where teams might overlook challenges while trying to validate their own ideas. This is why architects need to balance visionary thinking with the practical forces of doubt, skepticism, and experimentation.

Real-World Examples of Vision in Action

Let’s look at some examples where vision and belief sparked technological transformation, but critical evaluation ensured those visions became reality:

The Internet

- Visionary spark: Think about visionaries like Vannevar Bush and J.C.R. Licklider, who dreamed of a global interconnected network—what Licklider dubbed an “Intergalactic Computer Network”.

- Balancing belief: This imaginative vision only became a reality through decades of tackling challenges around protocols, bandwidth, and reliability—all grounded in rigorous engineering and continuous improvement.

Agile Software Development

- Visionary spark: The Agile Manifesto captured a belief that software development could be quicker, more adaptable, and more centered on human needs.

- Balancing belief: Agile success hinges on teams continuously testing and refining their approaches. When belief outpaces reality—like in cases of “Agile in name only”—results can fall short.

The DevOps Movement

- Visionary spark: DevOps emerged from the belief that breaking down silos can enhance collaboration, speed, and quality in software delivery.

- Balancing belief: DevOps thrives when teams take a pragmatic approach—adapting tools, processes, and culture thoughtfully, rather than following a strict dogma.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML)

- Visionary spark: From Alan Turing’s pioneering ideas to today’s advancements in NLP, computer vision, and generative models, belief in AI’s potential is pushing the envelope of innovation.

- Balancing belief: Responsible AI development demands rigorous testing, ethical considerations, and a grounded understanding of limitations—balancing hype with humility.

Vision Without Balance Is Risky

While vision and belief are crucial, they alone aren’t enough. Without curiosity, we miss out on exploring alternatives. Without doubt, we risk overlooking our assumptions. And without skepticism, we could be building illusions on shaky ground.

The best architects are the ones who can inspire belief while remaining open to challenge and adaptation.

Final Thought: The Courage to Believe, the Discipline to Validate

In the realm of architectural leadership, vision infuses innovation with meaning. It transforms a scattered collection of ideas into a united movement, rallying people around shared goals and providing long-term focus in our fast-evolving tech landscape.

But let’s keep this in mind: belief must be tested, and vision must be earned—not just through ideas, but through execution.

When architects strike a balance between belief and rigor, they don’t simply follow trends—they help shape the future.

Skepticism: The Critical Lens That Fuels Innovation

Let’s talk about skepticism. It often gets a bad rap, seen as cynicism or resistance to change. But in the world of IT architecture, skepticism is more like a smart, informed reality check. According to Wikipedia, it’s about having “doubt regarding claims that are taken for granted elsewhere.” This means skepticism helps organizations steer clear of unexamined assumptions and potential pitfalls.

When doubt prompts us to seek more certainty, skepticism nudges us to pause and reconsider—sometimes even to abandon certain ways of thinking. It raises essential questions: Is this really feasible? Is this solution based in actual reality?

Skepticism ≠ Pessimism

Here’s the important part: skepticism isn’t about dismissing innovation. It’s about ensuring that any new ideas are thoughtful, practical, and grounded in the real world. Fred Brooks’s classic paper, “No Silver Bullet—Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering,” serves as a great example. He challenged the notion that a single breakthrough could drastically improve software productivity. Instead, he argued for progress through smaller, more feasible innovations.

Skepticism is not pessimism—it is realism tempered with experience.

How Skepticism Shapes IT Architecture

In the realm of IT architecture, skepticism plays a pivotal role in:

- Evaluating new trends critically

- Identifying hidden costs or complexities

- Preventing over-engineering or the premature adoption of unproven technologies

That said, unchecked skepticism can also create problems. It can lead to missed opportunities, stifle promising innovations, and breed a culture of stagnation. When skepticism becomes a reflex instead of a reasoned approach, it slides into unproductive negativity.

So, what we need is practical skepticism. This goes beyond instinct; it requires deep knowledge, experience, and a well-rounded perspective.

Real-World Examples of Constructive Skepticism

Let’s look at some real-life examples where skepticism had a positive impact:

Monolith vs. Microservices

- Skeptical insight: Microservices seem great for flexibility and scalability, but early adopters raised concerns about distributed complexity and communication overhead.

- Impact: This skepticism led to hybrid models—like modular monoliths—that preserve simplicity while offering scalability. The result? Tailored solutions that truly fit the problem.

Blockchain Everywhere

- Skeptical insight: Blockchain was touted as a magic solution for everything from supply chains to voting systems. Critics questioned whether its complexity was genuinely necessary.

- Impact: This critical viewpoint prevented many organizations from misusing blockchain. Instead, they focused on traditional databases when decentralization wasn’t vital.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Hype

- Skeptical insight: Skeptics pointed out the exaggerations surrounding general AI and autonomous vehicles, particularly regarding safety and data bias.

- Impact: This grounded view fostered ethical AI development, promoting realistic use cases (think narrow AI) and better safeguards for deployment.

Agile Methodology Skepticism

- Skeptical insight: Agile doesn’t work for every team. Architects highlighted concerns where Agile was applied without considering team maturity, product type, or architectural needs.

- Impact: This pushback led to innovative hybrid methodologies, blending Agile practices with upfront planning, particularly for larger systems.

Serverless Computing

- Skeptical insight: While serverless platforms promise speed and scalability, skeptics pointed out issues like cold starts and vendor lock-in.

- Impact: Many teams adopted selective serverless strategies, using them for event-driven workloads while keeping traditional infrastructure for core systems.

Skepticism as a Leadership Skill

Skepticism is arguably one of the most intellectually demanding skills for leaders. Unlike doubt or curiosity, which can rely on structured questions, skepticism leans on judgment, pattern recognition, and a broad awareness of systems.

There aren’t many structured tools for skepticism. Instead, it comes from experience, deep expertise, and a willingness to challenge the status quo.

The best architectural leaders aren’t just contrarians—they’re constructive skeptics. They know when to question the hype and when to champion tried-and-true solutions.

Final Thought: Finding Balance

In the end, skepticism is more of a safeguard than a roadblock. It invites us to think critically, ensuring that our innovations truly resonate with the realities we face. Balancing healthy skepticism with openness to new ideas can lead to solutions that are not just innovative, but genuinely effective.

Integrating the Compass: Finding Balance in Sustainable Architecture

Imagine the four points of a compass—curiosity, doubt, vision, and skepticism. Rather than being opposing forces, they actually complement each other beautifully. When we strike a balance among these motivators, we lay the groundwork for resilient and forward-thinking IT architecture.

In high-performing teams, these motivators work hand in hand:

- Curiosity ignites our desire to explore and learn new things.

- Doubt encourages us to test and validate our ideas.

- Vision keeps us focused on a clear direction and purpose.

- Skepticism makes sure we stay grounded in reality.

If we lean too heavily on any one of these forces, we might find ourselves off-balance. For example, too much curiosity can lead to uncritical innovation, while too much skepticism might result in stagnation. The key? When we use all four motivators together, we make decisions that are bold yet cautious, strategic yet adaptable, and ambitious yet realistic.

Cultivating Balance Through Questions

A great way for IT architects to help their teams integrate these forces is by regularly asking the right questions:

- Curiosity:

- Are we actively exploring new technologies and approaches, or are we just sticking to what we already know?

- Are we encouraging room for experimentation and learning throughout the organization?

- Vision:

- Do we have a clear architectural direction guiding our efforts?

- Are we just reacting to trends without a cohesive strategy in place?

- Doubt:

- Are we using the right methods—like testing and validation—to reduce uncertainty and boost our confidence in our solutions?

- Are we willing to refine our ideas when necessary?

- Skepticism:

- Are we critically examining our own assumptions and biases?

- Are we being skeptical of our own preferred solutions, or just questioning those from others?

Final Thought: Leading with Balance

IT architects play a crucial role in orchestrating this balance. By blending curiosity, doubt, vision, and skepticism, they can create environments where:

- New ideas are explored boldly but assessed wisely,

- Strategy informs action without stifling innovation,

- Critical thinking enhances outcomes, rather than slowing them down.

The aim isn’t just to pick a direction but to build a compass that keeps the team moving forward with purpose, clarity, and confidence.

When these four motivators align harmoniously, organizations are not only better equipped to navigate complexities but also to embrace change and drive lasting innovation. Let’s embrace this balanced approach and see where it takes us!

To Probe Further

- The Four Points of the Research Compass, by Željko Obrenović, 2013

Questions to Consider

- How does curiosity drive innovation in your organization, and how do you prevent it from leading to unsustainable or risky decisions?

- In what ways can doubt contribute to the quality and robustness of your work, and how do you ensure that it doesn’t stifle innovation?

- How do you balance long-term vision and belief with the need for critical evaluation and validation in your decision-making?

- How do you cultivate constructive skepticism without allowing it to turn into cynicism that hampers creativity?

- When exploring new technologies, how do you ensure you follow industry trends and align them with a clear strategic vision?

- How can fostering a culture of curiosity, doubt, vision, and skepticism lead to more resilient and impactful solutions in your organization?

- What strategies can you use to balance risk-taking with rigorous validation in the innovation process?

- How does your organization support contributions driven by the four motivators: curiosity, doubt, vision, and skepticism?

- In what ways can skepticism be used as a tool for improvement without dismissing promising new ideas too early?

- How do you foster environments where curiosity and exploration are encouraged but tempered with thoughtful, critical evaluation?

On Being Architect |

|||

| ← | → | ||