Architecting Influence: Six Plays for Grounded IT Architects

IN THIS SECTION, YOU WILL: Understand how IT Architects can transform their effectiveness and foster a more collaborative, innovative, and grounded practice by consciously applying David Marquet’s six linguistic leadership plays to better navigate the complexities of modern technology environments.

KEY POINTS:

- IT Architects can significantly enhance their leadership and influence by adopting six key communication “plays” from David Marquet’s “Leadership is Language,” moving beyond outdated Industrial Age command-and-control styles.

- These plays—Control the Clock, Collaborate, Commit, Complete, Improve, and Connect—provide practical linguistic tools to foster better thinking (Bluework), more effective execution (Redwork), and stronger team engagement.

- Applying these plays helps architects build trust, flatten power gradients, encourage psychological safety, and unlock discretionary effort, leading to more robust architectural solutions and greater buy-in.

- The principles align directly with a “Grounded Architecture” approach by promoting data-driven decisions, collaborative networks, adaptability, and strategic impact within organizations.

- By consciously changing their language, architects can cultivate a more innovative, resilient, and effective engineering culture.

In today’s fast-paced world, architects have evolved beyond just technical designers. They’ve become strategic leaders and collaborators, which are essential for tackling the complexities we face and driving real business value. This shift calls for a sophisticated approach to leadership—one that moves away from the old “command and control “ mentality. Those outdated methods, which worked well in the Industrial Age, don’t fit in our modern, knowledge-driven environments, especially within IT. Here, architects often need to lead by influence rather than authority. So, I’d say communication isn’t just a nice-to-have skill; it’s the cornerstone of effective leadership.

A great resource that connects with my experiences is L. David Marquet’s “Leadership is Language.” As a former U.S. Navy Captain, Marquet shows how the words leaders choose can dramatically shape their team culture, effectiveness, and ultimately, success. He makes a compelling case that even small shifts in language can lead to big impacts on team performance and morale. This view challenges the traditional views of leadership and offers a “New Playbook” for the challenges we face today.

At the heart of this new playbook is the understanding that the nature of work has fundamentally shifted. Leadership in the Industrial Age was all about maximizing efficiency and ensuring compliance with tasks that were often physical and repetitive. In contrast, IT architecture demands a kind of work that is complex, cognitive, and collaborative. This kind of teamwork thrives on commitment rather than just compliance; it’s about unlocking that extra effort and innovation rather than just meeting the bare minimum. I’ve seen how adhering to outdated language in our leadership practices can hinder creativity and engagement. Organizations that fail to evolve their leadership language within architectural teams may struggle to innovate, adapt, and attract top talent.

The principles outlined in “Leadership is Language” resonate with my vision of Grounded Architecture. Marquet’s six leadership “plays” give us practical tools to enhance communication, encourage deeper thinking, and build more committed teams—all of which help us become more truly “grounded.” One crucial, yet often unspoken, challenge for IT architects is dealing with the “power gradient,” or the perceived hierarchical distance between people. I’ve noticed that steep power gradients can stifle creativity, suppress valuable insights, and block open communication, all of which are detrimental to effective architectural practices.

Navigating these dynamics is part of the job, especially in complex organizational structures. If we don’t make an effort to address these challenges through thoughtful language and communication, genuine collaboration—one of the key elements of Grounded Architecture—won’t thrive. Marquet’s strategies can help flatten those gradients and encourage more inclusive and effective interactions, which I believe are vital for our success.

Setting the Stage: From “Redwork/Bluework” to Effective Action

Before diving into specific plays, let’s take a moment to understand a key concept from Marquet’s framework: the difference between “Redwork” and “Bluework.” This distinction is crucial because it helps us recognize the various operational modes within a team and underscores the need for a balance between them to achieve top performance.

Redwork is all about the “doing” or “execution.” It’s the phase where we focus on performance, efficiency, and reducing variability to achieve our goals. In the world of IT architecture, this could mean coding a proof-of-concept based on a solid specification, finalizing and documenting an architectural design, or implementing a system according to a detailed plan. During Redwork, the spotlight is on execution and meeting those predetermined objectives.

On the other hand, we have Bluework. This work represents the “thinking” or “decision-making” phase. Here, we embrace variability and dive into reflection, planning, strategic problem-solving, and collaboration. For IT architects, this is where we shine. Think of strategic design sessions, weighing different technological options, evaluating new tech trends, and holding workshops to tackle complex architectural issues.

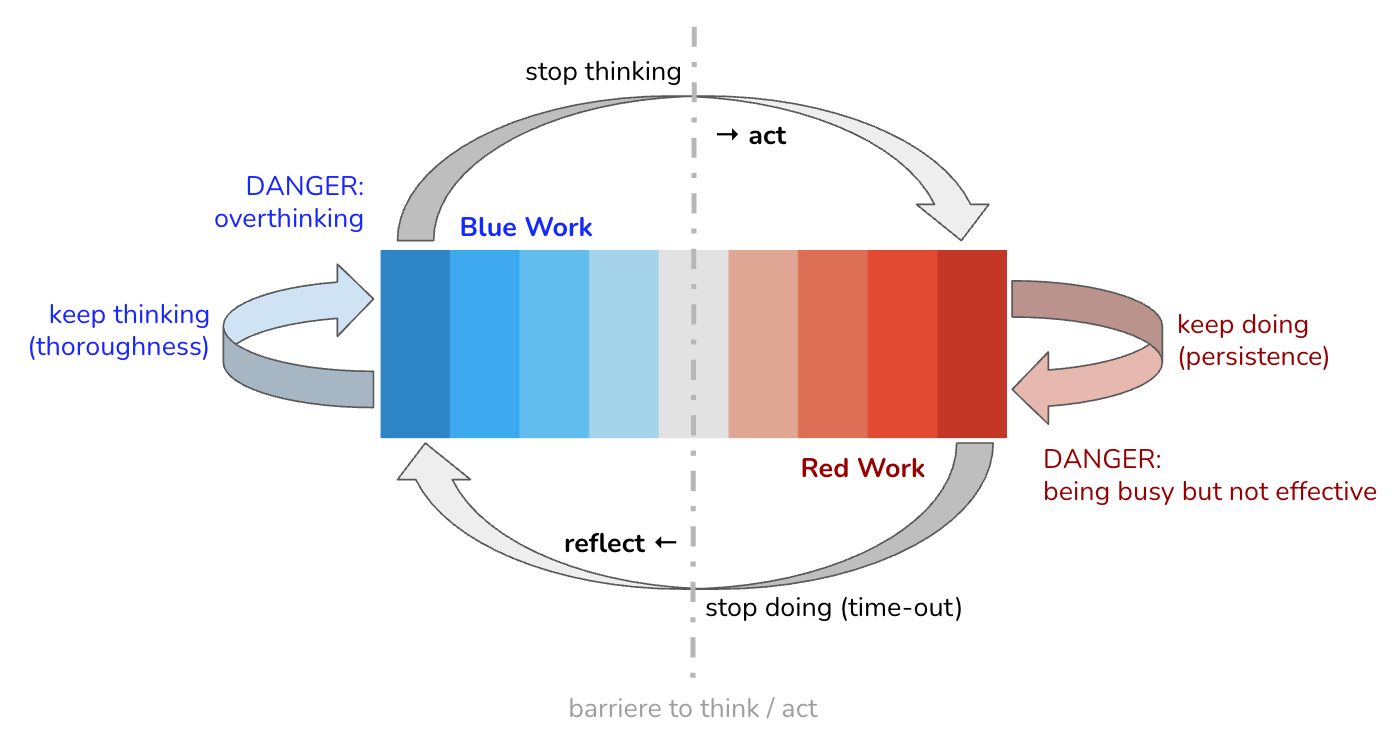

Marquet emphasizes the importance of oscillation between these two modes. Successful teams and their leaders need to be intentional about shifting between periods of Redwork and Bluework. Getting stuck in one mode while ignoring the other can lead to problems. For instance, excessive Bluework can lead to “analysis paralysis,” where we overthink everything, while an overload of Redwork without sufficient Bluework can result in hasty, poorly thought-out solutions.

Figure 1: This diagram illustrates the dynamic relationship between “Blue Work” (thinking/deciding) and “Red Work” (doing/executing). It highlights the necessity of consciously moving back and forth between these modes to lead more effectively. By creating a rhythmic cycle of thinking and doing, teams can pause to reflect, adjust, and act with intention—breaking the habit of defaulting to either execution or analysis.

Figure 1: This diagram illustrates the dynamic relationship between “Blue Work” (thinking/deciding) and “Red Work” (doing/executing). It highlights the necessity of consciously moving back and forth between these modes to lead more effectively. By creating a rhythmic cycle of thinking and doing, teams can pause to reflect, adjust, and act with intention—breaking the habit of defaulting to either execution or analysis.

For IT architects, this Redwork/Bluework framework is incredibly relevant. Our roles often require significant time spent in Bluework—strategic thinking, careful design, and thorough problem analysis are foundational to sound architecture. Yet, the constant push for quick delivery in many IT settings can inadvertently trap teams, including architects, in a relentless cycle of Redwork, leaving little room for essential thinking time. By identifying the team’s current “work mode,” architects can tailor their approach and language to either foster deeper thinking or drive effective execution.

When we fail to manage the balance between Redwork and Bluework, we can easily fall into common traps. Symptoms like “analysis paralysis,” where teams get bogged down in endless discussions due to excessive Bluework, or “rushed, flawed implementations,” which occur from insufficient thinking before jumping into Redwork, are all too familiar. Marquet’s strategies, like “Control the Clock” to encourage Bluework or “Commit” to shift into Redwork, provide practical tools for navigating these modes effectively.

Additionally, Marquet advocates for a democratization of Bluework. It shouldn’t just be the domain of architects or senior leaders; everyone should have a seat at the table. This perspective challenges the traditional view that sees architects as the lone “thinkers.” For a “Grounded Architecture” approach, which champions collaborative networks, architects should actively engage all team members in Bluework activities—be it design sessions or problem-solving workshops. This inclusivity enhances the decision-making process by bringing in diverse perspectives and fostering a shared sense of ownership among the entire team.

By adopting this balanced approach, we can foster stronger teams and achieve better outcomes. So, let’s keep the conversation going about how we can implement these ideas in our work environments!

The Six Leadership Plays in the Architect’s Arena

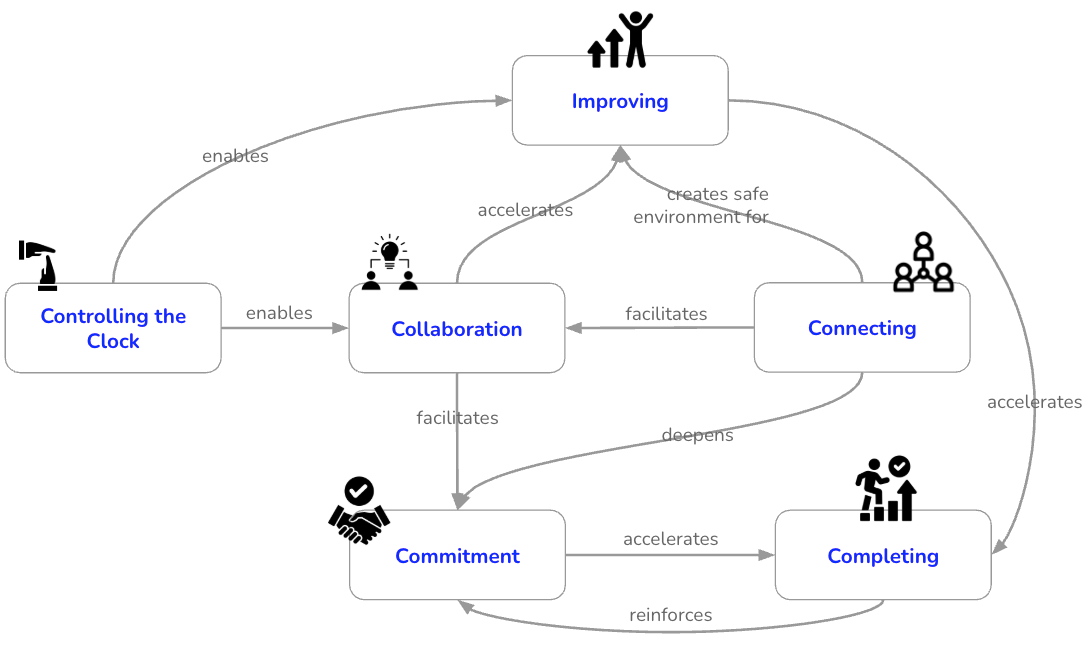

David Marquet introduces six powerful “plays” that can help leaders transform their communication and boost their team’s performance. These strategies represent a fresh approach to leadership, stepping away from the outdated methods of the Industrial Age. In Figure 1, you’ll see a circular framework that shows how IT Architects can increase their effectiveness. By intentionally applying Marquet’s six linguistic leadership plays—Control the Clock, Collaborate, Commit, Complete, Improve, and Connect—they can create a more collaborative, innovative, and grounded work environment.

Figure 2: David Marquet’s six linguistic leadership plays and their key interdependencies.

Figure 2: David Marquet’s six linguistic leadership plays and their key interdependencies.

The following table provides a concise overview of these plays and their relevance for IT Architects:

| Play | Shift From | Key Benefit for IT Architects | Key Marquet Phrase/Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control the Clock | Enables strategic pauses, better decisions, reduces errors | “Make a pause possible,” “Shift to Bluework” | |

| Collaborate | Leverages collective wisdom, fosters innovation, builds buy-in | “Let the doers be the deciders,” “Vote first, then discuss” | |

| Commit | Drives ownership, unlocks discretionary effort, ensures follow-through | “Commit to learn, not just do,” “Discretionary effort” | |

| Complete | Provides closure, facilitates learning, focuses on outcomes | “Chunk it small,” “Celebrate success” | |

| Improve | Cultivates a learning culture, continuous enhancement, reduces fear | “What can we learn?” “How can we make it better?” | |

| Connect | Builds trust, encourages psychological safety, authentic engagement | “Flatten power gradients,” “Trust first” |

Play 1: Control the Clock, Don’t Obey the Clock

Let’s talk about the “Control the Clock” play. This approach is all about knowing when to hit the pause button. Think of it as a way to carve out some space for thinking, reflection, and decision-making instead of just rushing from one task to another. It’s a response to that constant pressure we all feel to “do” and push through.

As leaders, it’s our job to ensure we allow for these pauses. It’s not just about creating that space; it’s about actively encouraging it, especially when teams are deep in their work and might not even realize they need to take a break. For example, a statement like, “We have time to do this right, not twice,” conveys a clear message that taking a moment to think things through is not only acceptable but also encouraged.

IT architects often work under intense pressure to deliver solutions at lightning speed. The “Control the Clock” technique empowers us to squeeze in some essential moments for those strategic architectural reviews. This technique not only ensures we stay aligned with the bigger picture but also helps us dodge expensive mistakes that often come from hasty decisions. It’s a great shield against the trap of “solutioneering,” which occurs when we jump to conclusions without fully understanding the problem or considering different approaches—something that’s all too common in the fast-paced IT world.

Here are a few examples:

-

Scenario 1 (Design Phase): Imagine an architect leading the design of an important new system. They notice the team is jumping too quickly onto a specific technology choice. This architect might step in and say, “Hold on, let’s put the ‘how’ on pause for a second. Are we all clear on the ‘what’ and ‘why’? What are the two or three core problems this component needs to address?” This wording nudges the team from Redwork (choosing a tool) back to Bluework (clarifying what needs to be solved).

-

Scenario 2 (Incident Response): Picture a significant system outage. Instead of just giving orders, an architect could call for a brief “Bluework huddle”: “Alright, team, let’s take ten minutes to step back. What do we know? What are our top two hypotheses about the root cause? What’s our safest next step in diagnosing this issue?” This practice of taking a timeout—even when things are chaotic—helps make pausing a regular part of the process.

-

Scenario 3 (Agile Context): An architect might even proactively slot in “architectural reflection” sessions during sprint planning or review meetings. This reflection ensures the team dedicates time to think through upcoming tasks and address any technical debt. For example: “Before we dive into these user stories for the next sprint, let’s take 30 minutes to discuss the architectural implications of Feature X and any possible long-term impacts.”

Mastering the art of “Controlling the Clock” is not just vital for strategic thinking but also sets the stage for genuine collaboration (which is Play 2) and meaningful improvement (Play 5). Without those intentional pauses, there isn’t enough room for diverse opinions, thorough discussions, or valuable insights to emerge. If architects don’t create these moments for reflection, conversations will likely feel rushed, dominant voices might take over, and true collaboration will slip through our fingers. Remember, improvement hinges on reflection, and that’s only possible when we take a moment to pause.

For architects, this play is a crucial tool for keeping our work tightly aligned with strategic objectives and data-driven insights rather than getting swept up in the whirlwind of short-term project demands. Rushing to meet deadlines can often lead to cutting corners in vital areas, such as data gathering or strategic thinking. By “controlling the clock,” architects make room to review data, consult with stakeholders, and ensure that our architectural decisions align with the broader goals of the organization. This practice also helps us avoid the dreaded “Ivory Tower” architect syndrome, keeping us connected to the practical realities and needs of the organization we serve.

Play 2: Collaborate, Don’t Coerce

The “Collaborate, Don’t Coerce” play promotes genuine collaboration by actively inviting and valuing diverse perspectives rather than allowing leaders to push their own agendas—whether subtly or overtly. A central tenet of this approach is to “let the doers be the deciders,” empowering those closest to the work to make meaningful contributions to decisions. Key techniques to foster this collaboration include “vote first, then discuss,” which helps prevent the group from anchoring on the leader’s opinion. Leaders are encouraged to speak last, after listening to others, and to cultivate genuine curiosity about dissenting viewpoints by asking questions like, “What do you see that we don’t?” Creating an environment of psychological safety, where individuals feel comfortable sharing their honest thoughts without fear of judgment, is essential for the success of this play.

Architects need buy-in and active participation from a diverse array of stakeholders, including developers, product managers, operations teams, and business units. While coercion might yield superficial compliance, genuine collaboration fosters deeper commitment, more robust solutions, and shared ownership. Complex architectural problems, which are common in modern IT, greatly benefit from cognitive diversity; collaboration is key to harnessing this collective intelligence.

Examples:

-

Scenario 1 (Technology Selection): An architect is tasked with selecting a new messaging queue technology for the organization. Instead of stating their initial preference, they present the problem, outline the selection criteria, and then ask team members to independently write down their top one or two choices along with their reasoning (“vote first”). Following this, the architect facilitates a discussion, ensuring all voices are heard by asking clarifying questions and exploring different perspectives. They provide their own assessment only after everyone else has had a chance to speak.

-

Scenario 2 (Design Review): During a review of a proposed microservice architecture, a junior engineer expresses a concern about potential data consistency issues. Instead of dismissing this concern or providing an immediate rebuttal, the architect responds with curiosity: “That’s an interesting point. Tell me more about that. What specific scenarios are you envisioning where consistency might become an issue? What do you see that the rest of us might be missing?” This approach validates the contribution and encourages deeper exploration.

-

Scenario 3 (Architectural Principles Co-creation): An architect facilitates a workshop with lead engineers from various teams to define a new set of architectural principles for the company. They provide a guiding framework and some initial examples but actively encourage the team to generate, debate, and refine the principles themselves. The architect acts as a facilitator and guide rather than a dictator, asking questions like, “Our goal is to co-create these guiding statements. What are the most critical principles we need to ensure consistency, scalability, and maintainability for our platform moving forward?”

The ongoing trend toward distributed systems, and cross-functional agile teams in IT makes the “Collaborate, Don’t Coerce” play increasingly vital. Architects operating in such environments cannot effectively dictate solutions from above; their success relies on their ability to facilitate, integrate, and harmonize diverse technical expertise and perspectives. An architect cannot be the foremost expert in every component of a complex, distributed system, so their capacity to collaborate effectively with specialists—rather than coercing them into a singular, preconceived vision—becomes crucial for architectural quality and adoption. This play is a direct enabler of leveraging the “collaborative networks” central to the Grounded Architecture philosophy.

However, a common pitfall for architects is “disguised coercion”—believing they are collaborating when, in fact, they are subtly steering conversations toward their preferred outcome. Architects, often being senior and highly experienced, might unintentionally coerce through the strength of their opinions, the way they frame questions, or by selectively amplifying certain viewpoints. This play requires genuine humility and a sincere willingness to be proven wrong or to adopt a solution that differs from one’s initial inclination. For some architects, this represents a significant mindset shift, moving away from traditional top-down approaches.

Play 3: Commit, Don’t Comply

The “Commit, Don’t Comply” play emphasizes obtaining genuine, internally motivated commitment from the team, which is essential for unlocking discretionary effort. This approach contrasts with mere compliance, which usually results in only the minimum effort necessary to meet requirements. Commitment is an active choice made by individuals and is often nurtured through true collaboration during the decision-making process. This play encourages commitment to learning (rather than executing tasks blindly) and commitment to actions (even when individual beliefs or preferences do not fully align with the chosen path). The linguistic shift from “I can’t” (implying an external force and fostering compliance) to “I don’t” (indicating internal resolve and commitment) illustrates this principle.

Architectural standards, patterns, and strategic decisions are only effective if development teams genuinely commit to their adoption and implementation. Compliance often leads to superficial adherence, workarounds, or even eventual abandonment. Significant architectural changes, such as platform modernization or the adoption of new paradigms, require deep and sustained commitment from engineering teams to navigate inevitable challenges and successfully complete the initiative.

Examples:

- Scenario 1 (Adopting a New Standard): After a collaborative process (as described in Play 2) to select a new API security standard, the architect seeks explicit commitment from the involved teams. They might say, “We’ve thoroughly discussed our options and collectively chosen this standard. What support do you need from the architecture team and from each other to fully commit to implementing this standard for all new services moving forward? What potential roadblocks can we anticipate now and plan for together?” This language positions the adoption as a shared goal and responsibility.

- Scenario 2 (Proof of Concept): An architect initiates a Proof of Concept (PoC) for a new, potentially transformative technology. Instead of merely assigning tasks, they frame the initiative to encourage a commitment to learning: “Our primary goal for this PoC is to learn whether this technology can effectively solve X problem for us and to gain a clear understanding of its operational complexities and integration challenges. Let’s commit to these specific learning objectives and the actions required to achieve them over the next two weeks.”

- Scenario 3 (Decision Disagreement): A team has decided on an architectural approach that the architect has some reservations about, though it’s not a critically flawed decision. The architect might express their support by saying, “While I see some potential challenges with this path, the team has made a strong case and collectively decided to proceed. I commit to supporting your decision and will help you succeed in its implementation. Let’s agree on the key actions, milestones, and check-in points to ensure we can address any issues that arise.” This shows commitment to the team’s chosen action, even if the architect’s personal belief isn’t absolute.

True commitment often results from effective collaboration. Attempts by architects to secure commitment without first engaging in genuine, inclusive collaboration are likely to yield, at best, superficial compliance. If architects skip or poorly execute the Collaborate play—for instance, by subtly coercing the team toward a predetermined solution—team members will not feel a sense of ownership over the decisions made. Therefore, their adherence will be driven by compliance (“I’m doing this because the architect said so”) rather than true commitment (“I’m doing this because I believe in its value, understand its rationale, and had a meaningful say in the decision”). This significantly impacts the quality, sustainability, and ultimate success of architectural implementations.

The “Commit, Don’t Comply” play is also vital for the effective functioning of adaptable governance models (nudging, taxation, mandates) as described within the Grounded Architecture framework. While mandates represent a top-down enforcement of compliance, mechanisms like nudging and taxation rely more on influencing behavior and fostering commitment rather than imposing strict adherence. These softer forms of governance aim to guide choices by making desirable architectural behaviors easier or more attractive, requiring a degree of voluntary buy-in or commitment from the teams.

Play 4: Complete, Don’t Continue

The “Complete, Don’t Continue” play challenges the Industrial Age mindset of continuous, undifferentiated, and often unending work. It emphasizes breaking down tasks into defined, manageable chunks with clear completion points. A key aspect of this play is the importance of celebrating successes upon completion and learning from each finished cycle. The principle of “Chunk it small, but do it all” is particularly relevant when dealing with high levels of uncertainty or complexity. This principle involves explicitly deciding when to stop a particular phase of work and having agreed-upon stopping criteria or definitions of “done”.

Architectural initiatives—such as platform migrations, system redesigns, or the rollout of new enterprise-wide standards—can be large, complex, and long-running. Breaking these substantial undertakings into smaller, completable phases or milestones is crucial for maintaining momentum, providing opportunities for iterative learning and adjustment, and fostering a sense of accomplishment within the team. This play helps architects avoid “architectural drift,” where designs are endlessly refined without delivering tangible value, or “analysis paralysis,” which can stall progress indefinitely.

Examples:

- Scenario 1 (Platform Modernization): An architect leading a multi-year platform modernization initiative works with teams to define clear, completable stages with measurable outcomes. For instance: “Stage 1: Migrate User Authentication Service to the new microservices platform. Target completion: End of Q2. Success criteria: 100% of user authentication requests handled by the new service with improved performance metrics.” Upon successful completion, the team celebrates this milestone.

- Scenario 2 (Design Spike): When faced with a complex new feature requiring significant architectural design, an architect initiates a time-boxed design spike (e.g., one week) with a specific, completable goal: “By the end of this week, we will have a documented decision on the data storage strategy for Feature Y, including a comparative analysis of the top two alternatives and the rationale for our choice. This document will represent ‘complete’ for this design spike.”

- Scenario 3 (Architectural Debt Reduction): Instead of pursuing a vague and potentially demoralizing goal like “reduce overall technical debt,” an architect collaborates with engineering teams to identify specific, completable pieces of technical debt to address each quarter. The successful refactoring or elimination of these items is then acknowledged and celebrated. For example: “This quarter, our focus is to complete the refactoring of the Legacy Billing Module’s outdated interface, thereby eliminating a significant source of maintenance overhead.”

The “Complete” play creates defined endpoints for work increments and incorporates celebrations of achievement, directly boosting team morale and reinforcing positive behaviors. This, in turn, creates a virtuous cycle, making future commitment (Play 3) easier to achieve. When successes are recognized and celebrated, it reinforces the specific behaviors that led to those successes, allowing individuals to feel a tangible sense of accomplishment. This positive momentum and the trust it builds make teams more likely to commit enthusiastically to the next defined chunk of work.

Furthermore, this play is vital for demonstrating tangible progress and showcasing the value delivered by the architecture function. This aligns directly with the Grounded Architecture principle, which emphasizes the need to show impact and execute effectively at scale. Architecture can sometimes be perceived as an abstract, slow-moving discipline, leading to accusations of architects operating in an “Ivory Tower,” disconnected from practical delivery. The Complete play focuses on delivering defined architectural outcomes in manageable chunks, making the value of architecture visible, measurable, and timely. This helps justify architectural investments, builds credibility for the architecture practice within the organization. Additionally, it provides clear points at which “Lightweight Architectural Analytics” can be applied to measure progress, impact, and adherence to architectural goals.

Play 5: Improve, Don’t Prove

The “Improve, Don’t Prove” play advocates for a fundamental shift in mindset—moving away from an environment where individuals feel the need to constantly prove their competence and the infallibility of their decisions. Instead, it fosters a collective focus on improving outcomes, processes, and shared learning. This play promotes a culture of curiosity and reflection, encouraging questions such as “How could we make this better?” or “What can we learn from this experience?” It develops a learning culture where mistakes and setbacks are seen not as reasons for blame or shame, but as valuable opportunities for growth and refinement. Leaders embody this mindset by openly reflecting on their actions and considering how they could have been improved.

Architecture is inherently an iterative and evolutionary process; initial designs are rarely perfect and must adapt to new information, changing requirements, and feedback from implementation. An improve mindset allows architectural solutions to evolve and adapt effectively. This play is also crucial for fostering psychological safety within teams, encouraging engineers and other stakeholders to identify potential issues or weaknesses in architectural designs or decisions without fear of retribution or of appearing incompetent.

Examples:

- Scenario 1 (Post-Incident Review): After a significant system failure traced back to an unforeseen architectural flaw, the architect leads a blameless post-mortem. The focus is entirely on learning and improvement: “What can we learn from this incident as a team? How can we improve our design process, review mechanisms, or monitoring capabilities to prevent similar issues in the future?”

- Scenario 2 (New Technology Adoption): An architect leads the introduction of a new software framework in the organization. Rather than demanding immediate perfection or creating pressure to prove the framework’s viability, they frame the initiative as an opportunity for improvement: “Let’s pilot this new framework on Project X. Our main goal is to improve our development velocity and code quality for this type of service. What metrics will help us understand if we’re achieving that improvement? What challenges are we facing, and how can we adapt our approach or the framework’s configuration to overcome them?”

- Scenario 3 (Architect Self-Reflection): An architect shares a learning moment with their team, modeling vulnerability and an “improve” mindset: “Looking back at the initial design for System Z, I realize I didn’t fully account for the long-term scalability needs under peak load conditions. That was an oversight on my part. How can we, as a team, build in more robust scalability checks and forecasting earlier in our design process next time to avoid this?”

The “Improve, Don’t Prove” mindset is fundamental to creating and sustaining a culture of psychological safety within technical teams. Without this safety, team members are more likely to hide mistakes, downplay concerns, or avoid flagging potential architectural flaws—all to avoid the risk of appearing incompetent or being blamed for problems. When the environment prioritizes proving, individuals naturally become risk-averse and defensive, which stifles learning and innovation.

Architects who champion the improve mindset actively cultivate the safety needed for open communication about what is not working. This dialogue is critical for identifying and addressing architectural weaknesses before they escalate into major issues. As a significant cultural enabler, this play supports the core themes of adaptability and continuous learning central to the Grounded Architecture philosophy. Grounded Architecture is designed for fast-moving global organizations and emphasizes the need for adaptability in architectural practices and solutions.

The “Improve, Don’t Prove” play institutionalizes the process of learning and adaptation. By consistently asking, “How can we make it better?”, architects ensure that both the architecture and the surrounding practices are continuously refined and enhanced. This approach aligns perfectly with the need for an adaptable and evolving architectural strategy capable of responding to changing business needs and technological landscapes.

Play 6: Connect, Don’t Conform

The “Connect, Don’t Conform” play encourages leaders to transcend the limitations of hierarchical roles and the implicit expectations of conformity. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of building genuine human connections with team members. This approach involves intentionally flattening power gradients, valuing individuals for their unique perspectives and contributions, and fostering an environment of mutual respect and trust. Leaders are encouraged to demonstrate vulnerability, show care for their team members’ thoughts, feelings, and personal goals, and extend trust first rather than waiting for it to be earned. The play contrasts the Industrial Age tendency to conform to hierarchical positions with the modern need to connect with others as individuals.

IT architects often find themselves in roles where they need to influence outcomes without having direct managerial authority over all stakeholders. In these situations, building trust and rapport through genuine human connection is far more effective than relying on job titles or perceived hierarchical standing. Additionally, understanding the diverse perspectives, motivations, and concerns of various teams—such as development, operations, security, and product management—is crucial for creating holistic, well-rounded, and widely accepted architectural solutions. This deep understanding is cultivated through connection, not conformity.

Examples:

-

Scenario 1 (Cross-Team Collaboration): An architect working on a complex, enterprise-wide initiative makes a deliberate effort to have informal conversations (e.g., virtual coffee meetings or brief one-on-one chats) with key members of different engineering teams. The purpose is not solely to discuss the project agenda but to better understand their experiences: “I’d like to understand your team’s perspective more deeply. What are your biggest pain points with the current platform, and what are your aspirations for how it could better support your work?” This indicates a care for people’s thoughts and feelings.

-

Scenario 2 (Handling Dissent): In a design meeting where a particular architectural proposal is being debated, one engineer persistently voices strong criticisms. Instead of shutting down the critique or becoming defensive, the architect employing the “Connect” play might say: “I appreciate you pushing back on this and clearly sharing your concerns. It’s evident you have strong reservations. Let’s ensure we fully understand your viewpoint. Help me see what you’re perceiving.” This language values the individual and their input, fostering a more open dialogue beyond simple role-based interaction.

-

Scenario 3 (Architect Admitting Uncertainty): When faced with a novel and particularly challenging technical problem for which they don’t have an immediate solution, an architect shares their uncertainty with the team: “Honestly, I don’t have a ready-made answer for this one. This is new territory for me as well. Let’s explore this challenge together. What are your initial thoughts, ideas, or even gut feelings on how we might approach this?” Admitting “I don’t know” demonstrates vulnerability, builds trust, and invites collaborative problem-solving.

“Connect, Don’t Conform” serves as an overarching strategy that enhances the effectiveness of all other leadership plays. Without genuine connection, mutual respect, and trust, attempts to truly Collaborate, gain deep Commitment, or foster a safe environment to Improve are likely to be less effective and more superficial. If team members feel they are merely expected to conform to their roles or to the perceived hierarchy—acting as cogs in a machine—they are less likely to openly share their best ideas, genuinely commit to decisions, and will certainly not feel safe enough to point out flaws or suggest improvements.

Connection builds the psychological safety and trust that are essential for positive team interactions. It forms the relational foundation upon which effective architectural leadership is built. This play is crucial for nurturing collaborative networks and fostering an understanding of human factors, which are central pillars of the Grounded Architecture philosophy. Grounded Architecture emphasizes the importance of Collaborative Networks and dedicates attention to Human Complexity, which includes understanding cultural differences and cognitive biases. The act of connecting is precisely how architects build these vital relationships.

IV. Conclusion: Integrating Leadership Principles into Your Architectural Practice

The six leadership principles outlined in David Marquet’s Leadership is Language—Control the Clock, Collaborate, Commit, Complete, Improve, and Connect—provide a valuable toolkit for IT Architects looking to enhance their leadership effectiveness. By adopting these linguistic shifts, architects can transform their leadership style from a traditional, potentially less impactful approach to one that is more empowering, collaborative, and results-oriented. These concepts are not just abstract theories; they are practical, actionable tools that can be implemented immediately through a conscious change in the language we use in our daily interactions.

Architects should start by observing their own language and the prevailing communication patterns within their teams and organizations. Which principles resonate most strongly with them? Which ones address the current challenges they face? Starting small, perhaps by focusing on intentionally applying one or two principles, can help build confidence and demonstrate tangible benefits. Consistent application of these principles by architects can create a positive ripple effect, influencing not only their immediate teams but also promoting a more constructive and innovative engineering culture across the broader organization. As architects model this new language of leadership, others may begin to adopt similar communication patterns. This can lead to a gradual but significant positive shift in how technical discussions are conducted, decisions are made, and how individuals and teams interact, ultimately fostering a more psychologically safe and innovative environment.

Embracing these leadership principles aligns directly with the core tenets of Grounded Architecture. By mastering this new language, architects can build stronger and more effective collaborative networks, make more robust and data-informed decisions by creating the necessary space for diverse input and thorough analysis, enhance the adaptability of their architectures and practices, and deliver greater strategic value to their organizations. The journey to becoming a truly Grounded Architect is, in many ways, a journey of mastering the language of modern leadership. This transformation is not a one-time event but a continuous path of improvement, similar to mastering any complex technology or methodology. It requires ongoing practice, conscious reflection, and a willingness to adapt and refine one’s approach over time. This commitment to evolving one’s language is a hallmark of an architect dedicated to not only technical excellence but also to impactful and empowering leadership.

Questions to Consider

- Which of the six leadership plays (Control the Clock, Collaborate, Commit, Complete, Improve, Connect) do you feel is most lacking in your current team interactions, and what’s one small linguistic change you could make this week to start addressing it?

- Think about a recent architectural decision or discussion. How could applying the “Control the Clock” play (e.g., calling a deliberate pause for Bluework) have potentially improved the outcome or the process?

- When was the last time you consciously used language to “Collaborate, Don’t Coerce”? How did you ensure diverse perspectives were heard before your own (e.g., “vote first, then discuss”)?

- Consider a current architectural standard or initiative. Are your teams truly “Committed,” or are they merely “Complying”? What language could you use to shift towards genuine commitment?

- How can you apply the “Complete, Don’t Continue” play to break down a large, ongoing architectural effort into smaller, more manageable, and celebratable milestones?

- Reflect on a recent project setback or architectural challenge. How could an “Improve, Don’t Prove” mindset have changed the team’s approach to learning from the experience?

- In what ways can you intentionally “Connect, Don’t Conform” to build stronger relationships and flatten power gradients with stakeholders outside your direct team?

- How often do you find yourself or your team stuck in “Redwork” (doing) without sufficient “Bluework” (thinking/planning)? What triggers could you establish to prompt a shift?

- How might the “power gradient” in your organization be subtly influencing architectural discussions, and what specific phrases from Marquet’s plays could help mitigate this?

- What is one “Industrial Age” leadership phrase you commonly use or hear that you could replace with a “New Playbook” alternative to foster better architectural outcomes?

On Being Architect |

|||

| ← | → | ||